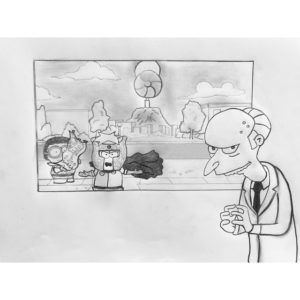

In a popular Simpsons episode, the diabolical Mr. Burns builds a giant disc to eclipse the sun and force residents into around-the-clock reliance on electricity from his power plant. A parody plan in South Park is withdrawn after Professor Chaos (Butters) is told that his scheme was already hatched in Springfield. It’s a pitch-perfect cartoon sendup with a foot firmly in reality: Burnsian obstruction by utilities looking to black out competition from solar, wind, and other environmentally-friendly electricity generators has led to sustained and systematic attacks on the constitutionality of state renewable portfolio standards.

The Dormant Commerce Clause

Drawing by Michael Krzywicki of DLD Lawyers

Public utilities prove their compliance with state renewable requirements by acquiring energy credits. Power plant operators normally receive one credit hour for each megawatt of electricity generated from renewable resources. Non-utility renewable energy producers can sell their credit hours to utilities for a premium on top of the income received from power sales in the wholesale electricity market. Utilities subject to state-level portfolio sourcing requirements can also invest in their own renewable power generation facilities to earn credits for the electricity they produce.

Whether utilities choose to earn their own credits or purchase them from others, they eventually pass the associated costs onto their ratepayers. The state policymakers’ hope is that utility customers will use more localized solar energy or wind generated electric power. In turn, the increased clean energy deployment will promote the public weal and internalize job creation and tax revenue.

To improve the political appeal of renewable energy sourcing requirements, some states have mandated that only renewable power facilities located within state borders will be eligible for energy credits. Often, more credit and hence greater value is granted to renewable power generated in-state. Still other states afford preferential treatment to facilities constructed with local labor or materials manufactured in state. Whatever their regulatory design, the discriminatory effect on interstate commerce and localized preferences render state climate and clean energy standards vulnerable to federal dormant Commerce Clause challenges. Mining interests worried about the sinking demand for coal and other fossil fuels in an increasingly renewables-fueled economy, large in-state electricity consumers driven by fear of rising power prices, and electric utilities forced to source a share of their salable power to end-users of renewable energy or purchase the output of independent power producers at a price premium are openly questioning the viability of these state pioneering policies.

While the Constitution’s affirmative grant of congressional authority to regulate interstate trade imposes no express limit on state authority, the Commerce Clause has long been understood to imply a negative or “dormant” corollary that denies state governments the power to discriminate unjustifiably against or burden the free flow of interstate commerce. The federal commerce power has been construed by the courts as a prohibition against protectionism by local regulatory measures designed to benefit in-state economic actors at the expense of out-of-state competitors. One important jurisprudential exception to this pro-competition thrust is the market participant doctrine.

When local government enters into locally regulated marketplace participation, for example: by owning or funding the enterprise receiving preferential treatment, the state regulation does not run afoul of the Commerce Clause. Thus, if a state pursues a legitimate local public interest through even-handed legislation, which effects only incidentally burden interstate commerce, the pertinent regulation will be upheld unless a court finds the imposition clearly excessive in relation to the putative local benefits. The Supreme Court has made clear, however, that shielding in-state industries from outside competition is almost never a legitimate local purpose, and state laws with the practical effect of regulating extraterritorial commerce will be subject to a virtually per se rule of invalidity. See, e.g., Wyoming v. Oklahoma, 502 U.S. 437, 454–455 (1992).

A Colorado requirement that all renewable energy used to meet South Park’s portfolio standards be generated within the state itself would almost certainly be struck down. Likewise, requiring energy providers to obtain a certain amount of renewable energy from in-state resources would fair no better under the per se test. A Springfield law forbidding Mayor Quimby to credit wind or solar power coming from out-of-state Shelbyville against the required use of renewable energy by Springfield’s Nuclear Power Plant would trip over an insurmountable constitutional objection made by lawyers for C. Montgomery Burns. Springfield cannot, without violating Article I of the Constitution, discriminate against out-of-state renewable energy. To pass muster, Springfield would have to demonstrate that its regulation serves a compelling state interest, and that this end could not be served so well by any available nondiscriminatory means.

The Supremacy of Federal Antitrust Law

Alternatively, Springfield might opt to have its state regulators set rates for power sales from renewable generators to its nuclear-powered electricity station through feed-in tariffs. This would guarantee out-of-state generators access to the local power grid by requiring Burns to purchase the power output of these independent producers at above-market rates and tend not to raise dormant Commerce Clause concerns. However, Burns’ lawyers may argue this plan’s features are preempted by federal antitrust law, and thus it places Springfield in violation of the Supremacy Clause. That’s because the Federal Power Act reserves ratemaking authority in these types of wholesale transactions for the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). What little ratemaking control Springfield does have in policing its public utilities authorizes it only to set rates up to the cost that Burns’ utility plant avoids by not generating the electricity itself or purchasing it from another source. See Hughes v. Talen Energy Marketing, 578 U.S. (2016) (upholding FERC jurisdiction over wholesale power markets against state energy policies, but under a tight definition); c.f. Atco Finance Ltd. v. Klee, (construing Hughes narrowly to uphold Connecticut’s right to engage in renewable energy solicitations).

After denying certiorari to review the Second Circuit’s narrow reading of its Hughes precedent, the issue seemed primed for resolution by the Court in 2018. The high court agreed to hear an Arizona utility’s appeal of a Ninth Circuit decision that a rooftop solar company’s antitrust lawsuit against the utility could move forward. SolarCity, a wholly owned subsidiary of Tesla Motors, had sued Salt River Project, a utility regulated by Arizona, over the utility’s 2015 decision to charge fees to those individuals operating solar energy power systems, many of which were installed by SolarCity.

In the lawsuit, SolarCity claimed that these fees were implemented to make rooftop solar energy systems too expensive to be competitive, in violation of federal antitrust laws. Salt River Project moved to dismiss the lawsuit on the basis that its rates and fees were determined by a statutory pricing process, and it was therefore immune from federal antitrust laws under the doctrine of state-action immunity.

The district court denied the motion to dismiss based on state-action immunity and refused to certify that ruling for interlocutory appeal. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit held that the utility could not invoke the narrow collateral-order doctrine to appeal the district court’s rejection of its state-action immunity defense, because the state-action immunity doctrine provided immunity from liability, not immunity from suit.

This ruling was in line with prior decisions by the Sixth and Fourth Circuits but was in contrast to opposite holdings by the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits. However, the Court’s grant of certiorari was ultimately dismissed, leaving open the question of whether state-action immunity denied to public utilities is appealable. SolarCity Corp. v. Salt River Project, 692 F. App’x, appeal dismissed, 859 F.3d 720, cert. dismissed per stipulation, Salt River Project v. Tesla Energy Operations, Inc., 138 S. Ct. 1323 (2018) (mem.).

The looming question remains: is Springfield powerless to stop Mr. Burns from blocking the sun, not for the least of which reasons why is that American law no longer recognizes a right to ancient lights by negative easement; or can Springfield manage to escape the shadow of its blackhearted nuclear reactionary?

Little clarity or consensus came either from the Sunshine State this year, after the Florida Supreme Court decided in June that a group of industrial power users were procedurally barred from claiming that the Public Service Commission improperly granted cost recovery for solar energy projects under a prior settlement agreement, which resolved to increase utility base rates for such projects but was left unchallenged by the group at the time it was before the Commission or in appeal of the administrative order. Florida Indus. Power Users Group v. Brown, 273 So. 3d 926 (Fla. 2019).